Thomas O'Donnell, Ph.D., Principal Analyst, Office of Academic Diversity

twodonnell@ucdavis.edu

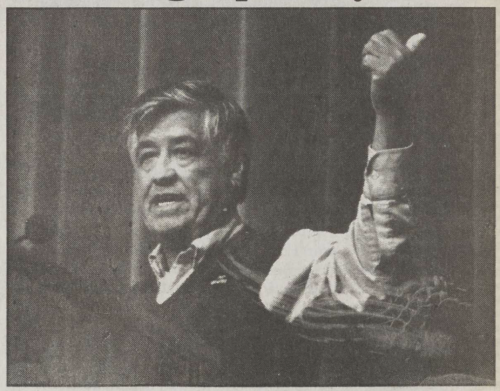

March 28, 2023–As noted in a previous article on the importance of supporting farmworkers by many Chicana/os at UC Davis, United Farm Workers union (UFW) co-

founder César Chávez spoke on campus a number of times asking for support of the boycotts and strikes he led in response to the poor wages and dangerous working conditions most of the workers he represented faced every day.

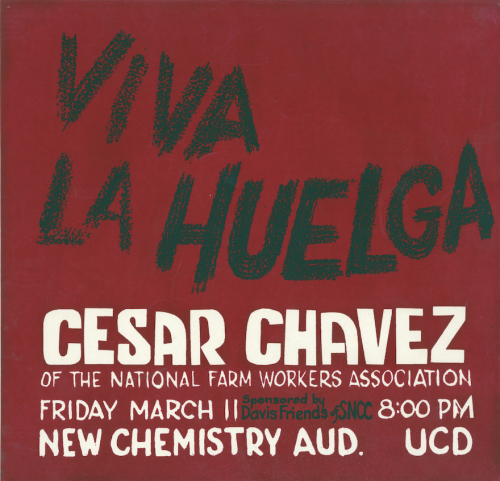

Chávez first visited UC Davis in 1966 as part of a Davis Friends of SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) presentation on the Delano grape-pickers strike that began the previous fall. The primary goal of the strike was to win union recognition for the workers to fight for, and in same cases, keep their current wages. Chávez delivered his remarks just days before the historic march from Delano to the state capital in Sacramento by "nearly a hundred striking farmworkers, most of them Mexican American and Filipino," a distance of 300 miles.

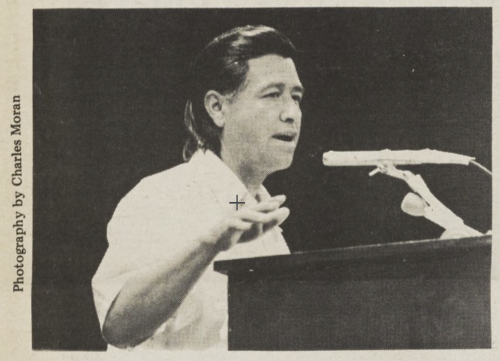

Five years later, when Chávez returned to the campus During his first visit on January 18, 1971, the UFWOC was engaged in a battle not only with lettuce growers but also with the Teamsters union that claimed to be the farmworkers' legitimate representative. (The United Farm Workers Organizing Committee renamed itself to the United Farm Workers in 1972.) During this visit he spoke about the principle of nonviolence that was at the center of UFW organizing efforts. He argued it was an effective strategy and maintained their principle of love. He also criticized, as many others at UC Davis would for years to come, the efforts “to develop farm machinery (as here in Davis), but nothing to help the people being displaced by it.” It would be up to “DQU to come up with a solution,” he said.

Only months earlier, a coalition of Chicanas/os and Native Americans occupied surplus land on the outskirts of Davis with the intention of establishing Deganawidah-Quetzalcoatl University (D-QU), a revolutionary new representation "of Indian and Chicano aspirations of self-determination."

On his return to UC Davis’s Freeborn Hall on May 1, 1973 as part of a fund-raising tour around Northern California, the UFW faced many of the same concerns as two years previous including “the harassment of organizers…fire bombs, vigilants [sic], beatings, and bloodshed,” and more recently faced “a vicious coalition of major grape and lettuce growers, the Teamsters, and the Nixon Administration.”

Chavez and the UFW had been battling with the Teamsters for years by 1973. In an article that originally appeared in El Malcriado–“the voice of the farmworker,” a newspaper started by Chavez to publicize their struggle–and reprinted in the Third World News in February 1971, growers entered into agreements with the Teamsters who claimed to represent the farmworkers. After initially securing an injunction against the UFW in late 1972, California’s Supreme Court “dissolved these injunctions on the grounds that evidence showed the growers had selected the teamsters as the union they wanted to do business with, and that there was no evidence to show the field workers wanted to be represented by the teamsters.” Despite a favorable ruling, it was difficult to enforce and according to Chavez, “Teamster goons,” and “motorcycle gangs” continued to physically assault UFW picketers. In fact, just before his arrival in Davis, the Teamsters claimed to have signed several contracts on behalf of the farmworkers with growers in the Coachella Valley.

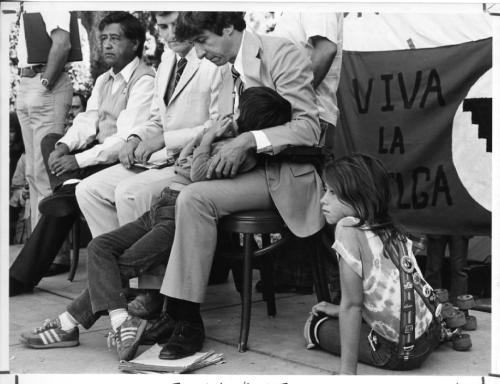

Chavez’s third visit to UC Davis, for which organizers expected more than 5,000 people to attend, came at the end of a national tour led by activists Jane Fonda and Tom Hayden. (In the Aggie’s coverage of the upcoming visit, notice of Chavez’s addition to the program was placed under headlines that Fonda was a leading choice by graduating law school students to be the commencement speaker and a counterprotest against Fonda that was being planned.) Chavez started the Friday’s events in front of “the biggest assembly ever in UCD history.” Despite not being invited as a speaker until Wednesday night, “when word got out…Chicanos from UCD, Indians from DQU and farmworkers, Mexicans, and Indios came as far away as Sacramento, Stockton, and Salinas…arousing the crowd that was the biggest assembly ever in UCD history.” He asked his supporters to continue their support of the boycott against California lettuce growers that had been going on for nearly a year by then. He also expressed concern about donations to the university by agribusiness to support mechanization research and warned that a disregard for the displaced workers that resulted from such technology “will impact on the whole society like the pesticide and nuclear issues have.”

His last visit to UC Davis in May 1991, which came just two years before his death, was part of a nationwide college tour and coincided with the campus Whole Earth Festival. Journalist Lynn Kusnierz explained that since the passage of the 1975 Agricultural Labor Relations Act, the UFW had signed contracts “with more than 160 growers, and has won the right to represent farm workers in 73 percent of all state-conducted elections.” Chavez once again asked the Freeborn Hall crowd to support the boycott of table grapes, the third such boycott, and on which had been ongoing since 1986. And, as he did in previous visits to UCD, criticized the use of pesticides that he claimed were responsible for rising cancer rates among poorer residents in the Central Valley.

Read more about the use of pesticides and farmworkers: Linda Lorraine Nash, Inescapable Ecologies: A History of Environment, Disease, and Knowledge (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).

Agricultural economist, UC Davis professor, and former director of Chicana/o Studies Refugio Rochin said about Chavez: “Certainly he transformed the image and roles and rights of farm workers in California, and influenced farm workers throughout the United States more than anyone else.”

You can read more about this project here: Writing Our HSItory, The Project

If you are interested in contributing to this project, please take a look at the Suggested Article Topics (or propose your own) and Article Submission Guidelines and then submit your work here for review and consideration.

The California Farm Workers' Struggle

In 1976, the editor of the journal The Black Scholar reprinted an article by Cesar Chavez, which discussed the farm workers' struggle for an effective farm labor law in California, that are out of their multi-year conflicts with the Teamsters union. You can read the article at:

Cesar Chavez, "The California Farm Workers' Struggle," The Black Scholar 7, n. 9 (June 1976): 16-19.

- Art Fernandez, “Cesar Chavez at UCD,” Third World News, January 18, 1971.

- Tom Brocato, “Chavez: Nonviolence is Natural,” California Aggie, January 19, 1971.

- Wallace Turner, “Teamsters Sued by Chavez’s Union,” New York Times, January 5, 1973.

- “Cesar Addresses Students,” Third World News, April 30, 1973.

- “Farmleader Chavez Speaks Today,” California Aggie, May 1, 1973.

- Dana Ahlgren, “Chavez Intensifies Battle With Teamsters,” California Aggie, 2 May 1973.

- Tracy Chapin, “Chavez Arrives Friday,” California Aggie, October 25, 1979.

- Greg Welsh, “Fonda, Hayden To Draw Crowd Of 5,000,” California Aggie, October 26, 1979.

- Jerry Hirsch, “Chavez Says Lettuce Strike Still On,” California Aggie, October 29, 1979.

- Rene Aguilera, “Hayden, Chavez, Fonda: ‘Coming Home’ to Davis,” Third World Forum, November 6, 1979.

- Lynn Kusnierz, “A Quest for Recognition,” California Aggie, May 10, 1991.

- Lisa Zeuschner, “Chavez on campus to promote grape boycott,” California Aggie, May 13, 1991.

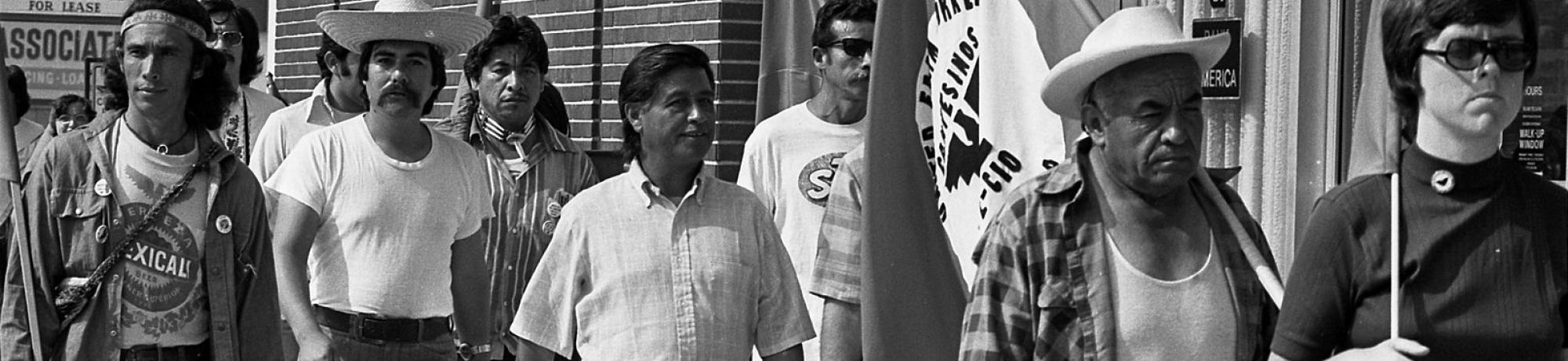

Header image: Cesar Chavez (center) on march from Mexican border to Sacramento with United Farm Workers members in Redondo Beach, California. Image: Los Angeles Times Photographic Collection at the UCLA Library.