Thomas O'Donnell, Ph.D., Principal Analyst, Office of Academic Diversity

twodonnell@ucdavis.edu

Defining Continental Colonialism

The concept of “continental colonialism,” has often been referred to as westward expansion, or even worse, Manifest Destiny. Recently, however, historians and other researchers have worked in a world more aware of the processes and consequences of colonization and see it as more than just a European phenomenon. In fact, it is precisely what the United States did over much of the North American continent after its independence from Great Britain.

This has not been the typical approach to understanding American history in part because there has long been a reluctance among Americans to consider ourselves a colonizing nation. It seems to go against our founding principle of self-rule. But thinking about the expansion of the United States into the West in these terms is important for at least three overlapping reasons:

(1) It forces us to think more explicitly about the political process of occupying new lands, which is to say that occupying lands in the west didn’t just happen because it was there, it required an exercise of power.

We need to think about those who occupied this region before the arrival of Americans and other European immigrants.

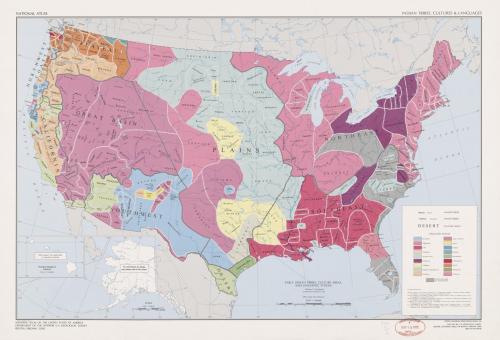

US history is often told from the perspective of ambitious men and women moving into a virgin land, an “unoccupied Eden” or as an uncivilized wilderness, waiting for Americans to come along and make it productive and free. But that was not the case. Millions of Native Americans had lived throughout the continent for tens of thousands of years before the arrival of first the Europeans and then Americans.

(2) The second reason, which follows from the first, to think about western settlement as a process of colonization is that it helps us avoid thinking teleologically about history.

Teleology: the explanation of phenomena by the purpose they serve rather than by postulated causes; explaining causes with the knowledge of outcome.

In history that means explaining causes with knowledge of outcome. For example, we know now that the United States extends from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. A teleological explanation to that would be to suggest that everything that happened between the first settlement of Virginia in 1607 to the acquisition of California from Mexico in 1848 would be to say, essentially, because that’s what the United States looks like. It makes history a straight line.

To think about westward expansion not as “manifest destiny” requires us to ask critical questions like “how did it come to be that the US encompasses this geography of North America?”

(3) The third reason to utilize the concept of colonization when talking about American expansion westward is that it draws attention to the political and military forces that made it possible. It emphasizes that America was quickly becoming a powerful nation with powerful energies pushing it beyond its colonial-era borders. The region we call the West was occupied by not only Native Americans for thousands of years, but for the previous three centuries, a series of foreign governments tried to colonize the land for themselves including the Spanish, French, Russians, and English.

An “Empire of Liberty”

An “Empire of Liberty”

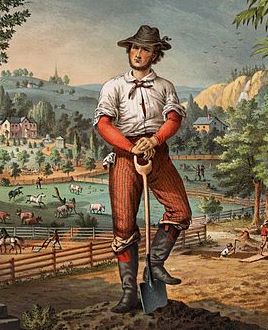

One of the tenets of the Democratic Republicans of the early republic, the party that largely coalesced around Thomas Jefferson (and thus sometimes referred to as Jeffersonians), was the political and economic equality of all Americans. The ideal personification of a Jeffersonian was the independent yeoman farmer.

Jefferson wrote about an “Empire of Liberty,” not an empire of mercantilism or military power but one that promoted freedom among Americans. This America was in contrast to the Whigs who envisioned a more industrial, urban, commerce-centric nation. The Jeffersonian response to that model required territorial expansion that would provide land for the nations’ citizen farmers and that might draw restless, landless people out of crowded eastern cities.

This effort to expand motivated Jefferson to pursue the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, that nearly double the size of the nation and by 1819, the US had successfully seized and negotiated the cession of Florida.

The West’s Native Americans and Mexicans

As they had from the first European footsteps on North America, Native Americans claimed and occupied much of the continent. That reality presented a barrier to the US government’s vision of a land filled with independent white homesteads as well as a belief in the legitimacy of their political claim to the land.

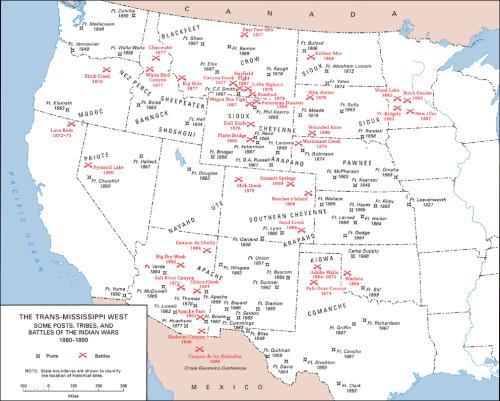

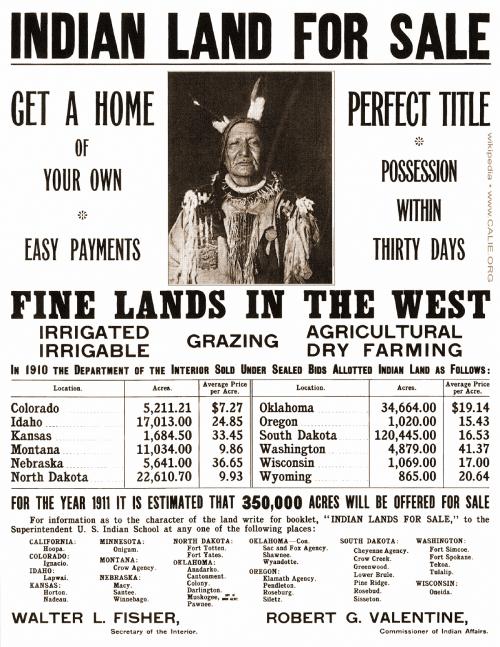

Following the Revolution, Congress operated as if the Native Americans of the interior were conquered peoples, allies of England who had lost the war and thus came under U.S. control. This approach worked for a short time as the U.S., through the use or threat of violence by the army, tribes such as the Iroquois, Chippewa, and Delaware conceded huge tracts of land and retreated to small, inadequate reservations. However, the often unfair “treaties” the U.S. imposed on the natives closer to settled areas and the so-called “slums in the wilderness” they were forced onto generated a great deal of resentment. In the Ohio Valley, that did not have the dense settlement of whites around the turn of the century, natives put up a much fiercer and more successful resistance.

By the late 1790s, the executive branch of the government shifted course by recognizing Indian rights to the land they inhabited and declared all future land transfers would come through treaty agreements. This treaty-based strategy proved effective initially as well. Native American leaders frequently ceded land in return for trade goods, yearly payments, and assurances that there would be no future demands. Reluctant tribal leaders could be persuaded to cooperate with warnings about the inevitable spread of white settlement or more cooperative chiefs could be found, anointed as the legitimate leader of a tribe, and bribed or bought.

For many native tribes in the nineteenth century, they were given the “choice” of assimilation or removal. The removal of the Cherokees from the Southwest along what has become known as the “Trail of Tears” is probably the most well-known example of Indian removal because it happened on a large scale over an extended period. However, it was essentially, a process that repeated itself many times over the nineteenth century.

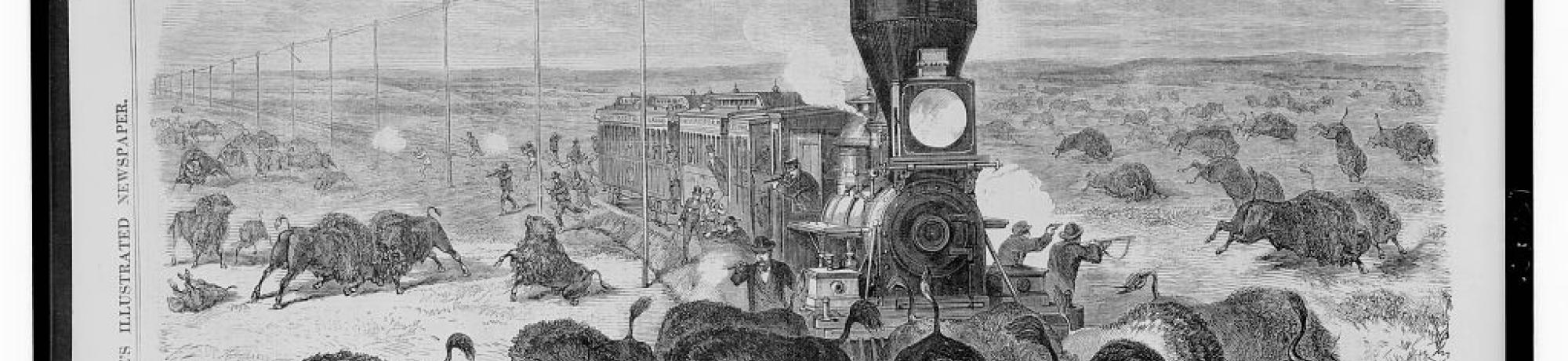

Just as the Civil War started, and then for the next three decades, there were continuous battles between the US and Indian tribes and over the course of the nineteenth century, Native Americans lost almost all of their land and were killed or relocated to reservations.

View an interactive map of Indian land dispossession produced by historian Claudio Saunt that documents the seizure of Indian land from 1776-1887.

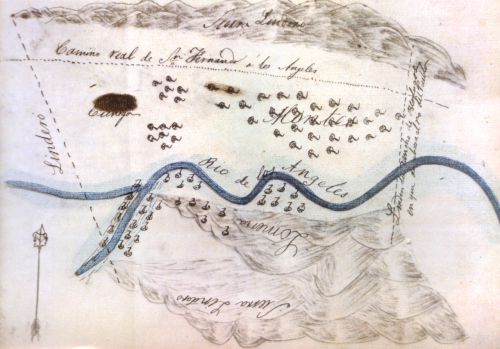

Another large-scale dispossession took place in the territory formerly claimed by Mexico until their defeat in the Mexican-American War in 1848.

One of the first acts by California politicians after statehood was to move against claims to the land by non-whites. These were typically enormous tracts of land held by Californios for cattle grazing that had very tenuous boundaries. Under the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, these grants had some legal protections. But in practice, ownership proved more difficult. In her book on Reies López Tijerina, a land-grant activists in the 1960s, UC Davis history professor emerita Lorena Oropeza explains Congress rejected Article 10 of the treaty that "would have automatically recognized the validity of all property held by Mexican citizens" and required them to prove ownership, which was exceedingly difficult (Oropeza, King of Adobe, 72).

For one, the grants were not defined with a degree of precision Americans were used to. Because they were for cattle grazing, exact measurements or boundaries were not necessary. Further, what constituted ownership also differed between Mexican and American law. Both required some sort of “improvement” or “use,” but Americans took that to mean intensive farming and fences.

To justify seizing land claimed by the former Mexican citizens, California legislators passed a law that required landowners to prove their grants were valid. This could be very difficult to do as it often required acquiring deeds or legal documents from their former government hundreds of miles away and tied up the matter in costly court battles for years. In the meantime though, the law stipulated that the land could be treated as open to squatters or contrary claims. This encouraged more Americans to move in and begin farming, which began a decades-long process of making agriculture a major industry in California.

In the Southwest, land previously held by Mexican citizens, 80% of it had been taken within 50 years of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Read the next article in this series:

Context: The Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862

Read More

The University of California Land Grab

Wide-scale U.S. higher education began in 1862 when the Morrill Act provided each state with “public” lands to sell for the establishment of university endowments. The public land-grant university movement is lauded as the first major federal funding for higher education and for making liberal and practical education accessible to Americans of average means. However hidden beneath the oft-told land-grant narrative is the land itself: the nearly 11 million acres of land sold through the Morrill Act was expropriated from tribal nations.

Learn more at the University of California Land Grab website

Tomas Almaguer, Racial Fault Lines: The Historical Origins of White Supremacy in California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008).

Ned Blackhawk, Violence Over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008).

Ari Kelman [UCD faculty], A Misplaced Massacre: Struggling over the Memory of Sand Creek (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015).

Lorena Oropeza [UCD emerita faculty], The King of Adobe: Reies López Tijerina, Lost Prophet of the Chicano Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

Daniel K. Richter, Before the Revolution: America’s Ancient Pasts (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2011).

Andrés Reséndez [UCD faculty], Changing National Identities at the Frontier: Texas and New Mexico, 1800-1850 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Karen R. Roybal, Archives of Dispossession: Recovering the Testimonios of Mexican American Herederas, 1848–1960 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

Vicki L. Ruiz [UCD emerita] From Out of the Shadows: Mexican Women in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Claudio Saunt, Unworthy Republic: The Dispossession of Native Americans and the Road to Indian Territory (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2021).