Thomas O'Donnell, Ph.D., Principal Analyst, Office of Academic Diversity

twodonnell@ucdavis.edu

By the late 1960s, Chicanas/os–their new, preferred term to describe their identity that distinguished them from earlier Mexican American activists–had developed a clear consciousness about their apparent second-class status in American society. And, according to Carlos Muñoz, “as a direct result of federal educational programs made possible by the civil rights movement and implemented especially during the Johnson administration,” universities such as UC Davis experienced a growth in their enrollment.[1] Those new college students continued the criticism of California’s public education started by the East Los Angeles high schoolers.

But it was not just admission that many were interested in. As noted in an earlier article, the participants at the symposium hosted by UMAS passed a resolution demanding a “full Chicano studies program.”[2] Referencing “El Plan de Santa Barbara” in an article describing the meaning of “El Cinco de Mayo,” a representative of M.E.Ch.A. connected the status of Chicanas/os to education. “Historically the University students, staff and faculty, in their ignorance and/or apathy have been a perpetuating factor in the oppression and exploitation of our Raza. This is realized not only by the lack of historical social and political courses dealing with the needs of our people, but also by the lack of courses dealing with the unique educational needs of our people.”[3]

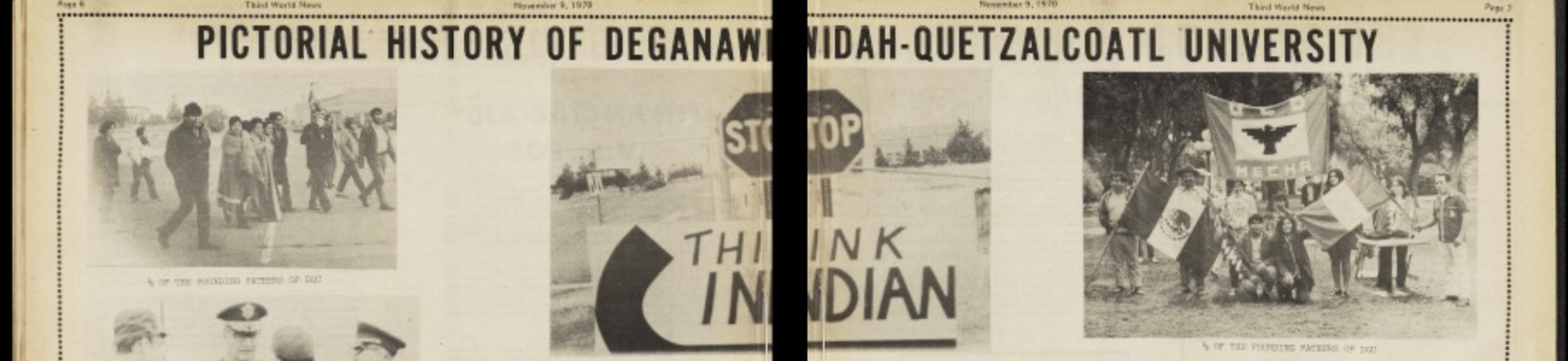

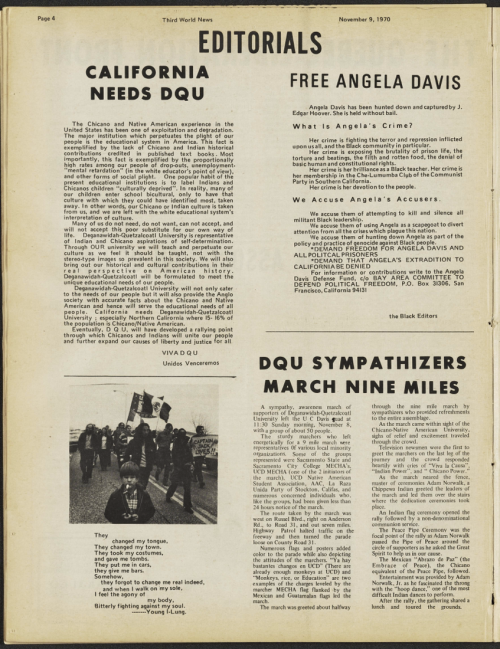

In a special issue of the Third World News published in 1970, an editorial explaining the importance of Deganawidah-Quetzalcoatl University–a newly established college in Yolo County that took the demand for a Chicana/o-oriented education to its logical conclusion–the author minced no words:

The Chicano and Native American experience in the United States has been one of exploitation and degradation. The major institution which perpetuates the plight of our people is the educational system in America. This fact is exemplified by the lack of Chicano and Indian historical contributions credited in published text books…In other words, our Chicano or Indian culture is taken from us, and we are left with the white educational system's interpretation of culture.[4]

You can read more about D-QU in a future article. See also Lorena V. Márquez, La Gente: Struggles for Empowerment and Community Self-Determination in Sacramento, chapter 4.

When students followed up on their resolution from the 1968 UMAS sponsored symposium for a culturally responsive curriculum they were met with resistance. By May of the following year, an article in the California Aggie noted the proposals submitted to Chancellor Mrak by the Black Students Union, UMAS, and the Asian-American Concern were told “take time.” That response did not go over well. One student journalist who had a regular column in the Aggie responded:

The need to act is now. If the administration, the faculty, the California taxpayer will not act, the students must act. While some may think that it is not the student’s role to affect change in society, I disagree. The responsibility for a better society rests with us all, students included. Because others refuse to take action is no excuse for us to do likewise. In fact, that is all the more reason for us to act with a more determined effort for on our shoulders falls the responsibility of doing what others are afraid to do.[5]

The concept of self-determination circulated widely in the Chicana/o Movement and was a unifying theme at the first National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference in March 1969 in Denver, Colorado, where participants drafted El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán. And then the next month at a historic conference at UC Santa Barbara where activists drafted El Plan de Santa Bárbara. The Santa Barbara Plan became a blueprint for Chicano Studies programs across the Southwest and here at UC Davis.

The agitation by students and faculty led to the formation of a Chicano Studies program in the fall of 1970. Faculty with expertise in Chicano history, the literature of the Mexican Revolution; and a linguist whose interests included bilingual education and teaching of English as a second language jointly developed 10 or 12 classes. Their objective was “to develop academic courses that dealt with the Chicano in his various aspects: historical, literary, linguistic, sociological, political, and economic. In some cases it became necessary to conduct classes without textbooks, since there were no books on the market that adequately met our needs.”[6]

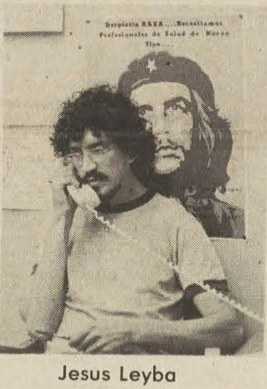

Just as important as the academic offerings, however, was the community that the new program, eventually department, offered students. Jesús “Xuy”/“Chuy” Leyba, was hired in 1968 and worked for Chicano Studies at UC Davis until 1990 as Assistant to the Chancellor for Chicano Affairs told the Aggie, “We see ourselves as a resource program basically–we act as a resource center to the campus, to the off campus community and to the student community within the area.”

Over the next decade, the Chicana/o Studies program grew impressively in response to the demands and work of students, staff, and faculty. By 1973 there were 11 affiliated faculty members and in 1974 it offered a Bachelor of Arts degree.[7] Future articles will highlight this growth and the numerous individuals and organizations–the topic of our next article–involved.

Read the next article in this series:

Chicana/o Student Organizations

Top image: A selection of photographs taken during the occupation of land and protests to support establishing D-QU. Third World News, November 9, 1970.

[1] Carlos Muñoz Jr., Youth, Identity, Power: The Chicano Movement, Rev. ed. (New York: Verso, 2007), 65. For an excellent examination of that earlier generation of activists see Christopher Tudico, "Before We Were Chicanas/Os: The Mexican American Experience in California Higher Education, 1848-1945," dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 2010.

[2] “UMAS Sponsors Symposium,” California Aggie, November 25, 1968.

[3] “M.E.CH.A.,” Cal Aggie, May 3, 1972.

[4] “California Needs DQU,” Third World News, November 9, 1970.

[5] “Jonathan Lewis Cares,” May 12, 1969.

[6] “Chicano Studies,” Third World News, May 1-7, 1972.

[7] Jeff Cook, “A Look at History,” Third World Forum, April 29, 1991. Chicana/o Studies formally became a department in 2008. “Ethnic Studies Programs in the College of Letters and Science,” UC Davis College of Letters and Science, https://lettersandscience.ucdavis.edu/ethnic-studies-programs-college-letters-and-science, accessed February 24, 2023.