Thomas O'Donnell, Ph.D., Principal Analyst, Office of Academic Diversity

twodonnell@ucdavis.edu

The final theme of the 1968 UMAS Symposium, which also connected very closely with the emphasis on student organizations and commitment to their community was the support for farmworkers in California. It was a cause central to the work in some measure of almost every Chicana/o activist at UC Davis in the 1970s. This was due in no small part to the fact that of the students, staff, and faculty that shared their family history, nearly all of them stated they or their parents were farmworkers.

Support for farmworkers was not unique to UC Davis, however. As noted in our article on student protests in the 1960s, the influence of the Civil Rights Movement on activists in California deserves recognition. Additionally, Carlos Muñoz identifies “the dramatic emergence of the farmworkers struggle in California led by César Chávez,” as motivation for college student activism.[1]

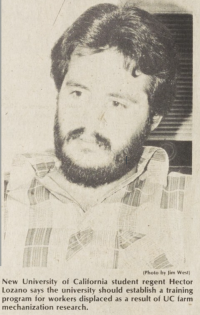

However, at UC Davis, many activists recognized the role the university played in the development of agriculture, especially the role in displacing farmworkers with technological innovations. In one of the earliest articles describing MEChA published in the California Aggie, student journalist Anne Nielsen explained that the group’s activities “are particularly relevant to its Davis chapter. Here in the Central Valley there is a large Chicano population of farm workers with a variety of problems that need attention…Members of M.E.C.H.A. feel that…it should be the duty of the University to support some means of taking care of the persons whose jobs it has made obsolete, means such as job retraining and/or a guaranteed annual income.”

Read a brief history of the UFW by Edward Salas, an Applied Behavioral Sciences major and member of MEChA, “Food For Thought,” Third World Forum, November 17, 1986, 11.

VIVA CESAR CHAVEZ! BOYCOTT SCAB LETTUCE AND GRAPES! BOYCOTT SAFEWAY! DOWN WITH THE TEAMSTERS!

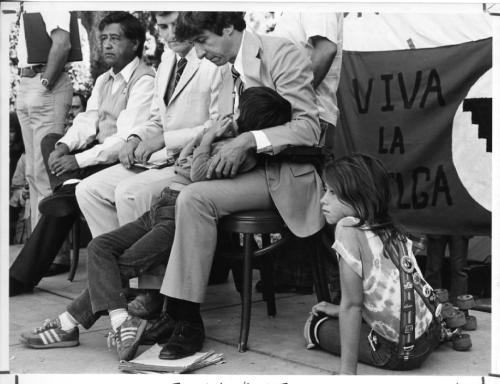

One of the most visible ways in which UCD students supported farmworkers was through their support of the United Farm Workers. Although there was some tension between Cesar Chavez and the broader student movement, he was still enormously popular in Davis. He spoke on campus several times including once in 1971, again in 1973, and then in 1979, when he wasn’t added to the program until two days before but “when word got out…Chicanos from UCD, Indians from DQU and farmworkers, Mexicans, and Indios came as far away as Sacramento, Stockton, and Salinas…arousing the crowd that was the biggest assembly ever in UCD history.” He last spoke at UC Davis in 1991.

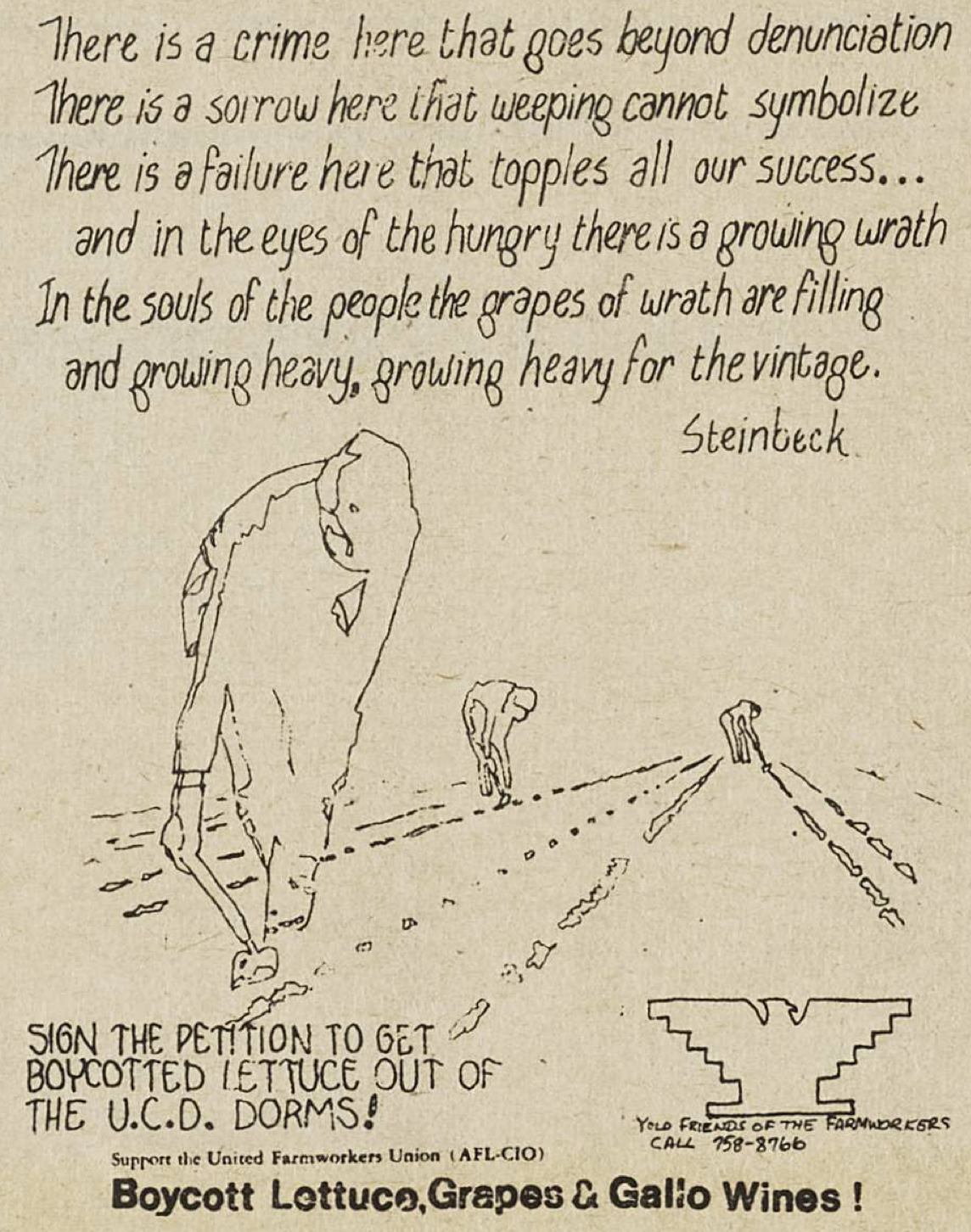

One of the earliest examples covered in the student newspaper of help for workers was a call by MECHA for contributions to a food caravan for striking farmworkers in Delano and the Salinas Valley in 1970. In 1973, UCD students supported the striking farmworkers during the lettuce and grape strikes by boycotting Safeway. Students in the residence halls voted on a referendum in 1975 to support the UFW’s boycott of lettuce and table grapes by banning them from the dormitory cafeterias.

One of the most significant victories in supporting farmworkers came in 1972 with their efforts in opposition to state proposition 22. The proposed statute, supported by agribusiness, would have prohibited strikes at harvest time, prohibited boycotts, and made organizing by workers considerably more difficult. In an article titled "This is MECHA," the author noted a coalition of the Chicano Students Association, the Chicano Medical Student Association, Chicanos in Health Education, and MEChA mobilized to rally student support “and campaigned vigorously” for its defeat.

The relationship between UC Davis and the agriculture industry and workers is extensive and we encourage interested authors to submit articles in support of this project. Readers can find a (growing) list of suggested article topics here and our article submission guidelines here.

If we return again to the themes identified from the UMAS symposium in 1968, the previous articles begin to highlight the ways in which Chicana/o students, staff, and faculty at UC Davis pursued their goals. Despite facing formidable historical and structural barriers, the fight to attain an education stretches over decades in classrooms, courtrooms, and the streets. Protesters understood the need to not only gain access to but also reform the curriculum to correct the biased knowledge which has supported their exclusion and to acknowledge their contributions to the nation’s success. Participants at the symposium understood that the changes they imagined would only come about through organized and coordinated efforts. The changes at UC Davis that have brought us to the cusp of becoming an HSI did not happen without the efforts of an untold number of people. This project is dedicated to telling those stories.

Read the next article in this series:

Read More:

“Behind the Battle of the Lettuce Fields,” Third World Forum, Volume 1, Number 18, 23 February 1971

Herman M. Levy, ”The Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975 - La Esperanza De California Para El Futuro,” Santa Clara Law Review 15, n. 4 (1975). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol15/iss4/1.

[1] Carlos Muñoz Jr., Youth, Identity, Power: The Chicano Movement, Rev. ed. (New York: Verso, 2007), 69-70. He also points to the land grant struggle of Reies López Tijerina in New Mexico as another source of inspiration. History professor emerita Lorena Oropeza wrote a definitive history of Tijerina and will be the subject of a forthcoming article. Lorena Oropeza, The King of Adobe: Reies López Tijerina, Lost Prophet of the Chicano Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019).