Thomas O'Donnell, Ph.D., Principal Analyst, Office of Academic Diversity

twodonnell@ucdavis.edu

In July 1862, a little more than a year after the start of the Civil War, President Lincoln signed “Act Donating public lands to the several States and [Territories] which may provide colleges for the benefit of agriculture and the Mechanic arts,” more commonly known as the First Morrill Act after its author, Vermont congressman Justin Morrill. We are frequently reminded that UC Davis is a land grant university. While the current interpretation or intent of that designation has not always been the one that guided past actions, what it means must be understood to activate its potential for change and equity in higher education.

From the National Archives

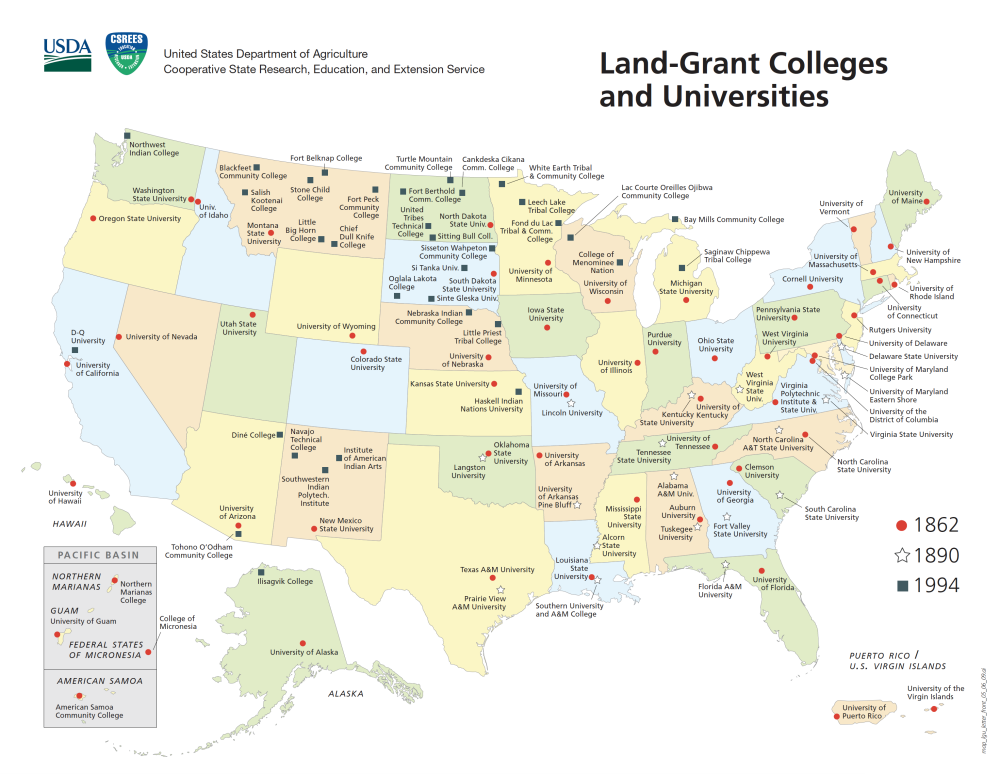

There are more than 70 land-grant universities across all fifty states, the District of Columbia, and several U.S. territories. The University of California’s ten-campus system are designated as this state’s land-grant institution. A map of all “1862s, 1890s, and 1994s”–so-called based on the year of the legislation that authorized their designation can be found on the U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture’s website.

Justin Morrill was born in New Hampshire in 1810. He represented Vermont in the House of Representatives from 1855-1867 and then in the U.S. Senate from 1867-1898. In his first congressional term, Morrill served on the House Committee of Agriculture and the Committee on Territories. As part of those duties, “he became convinced that more should be done to place the nation’s farming on a scientific basis.”[1] As a member of the Whig party, he believed the federal government should support the development of an integrated and capitalist economy; however, for most of the nineteenth century, federal investment in “internal improvement” projects such as transportation infrastructure or higher education found little support among most Americans. Thus, as historian Nathan M. Sorber explains in his comprehensive examination of the 1862 act, higher education developed “largely on its own terms through the support of religious denominations and local communities.”[2]

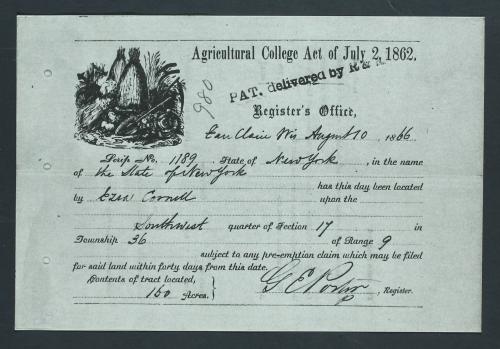

Shortly after he arrived to Congress, Morrill proposed a bill to establish agricultural schools with federal funding that was quickly defeated. A year later, he introduced a land-grant bill that allocated 20,000 acres of federal land for each senator and representative of a state to support colleges that offered instruction in “agriculture and the mechanical arts.” That bill was also defeated following a veto by President James Buchanan in 1859 who sided with southern states that flatly rejected the idea of federal intervention in matters traditionally left to the states and by western politicians that had fewer institutions of higher education and fewer representatives Congress to benefit from the enormous investment Morrill proposed. Finally, in a Congress controlled by the North, Morrill introduced the bill in the next legislative session (with the allotment increased to 30,000 acres per congressional representative) and it was signed by President Lincoln on July 2, 1862.[3]

From the beginning, as states established or designated existing institutions as “land-grant,” supporters disagreed over the law’s intent. A power agricultural movement known as the grange, saw the act as a way to reverse the disturbing trend of rural residents moving into the nation’s growing urban centers by training young men in the hands-on work of farming. Most universities they complained, were expensive and taught subjects for professional or sedentary occupations, not the hard and increasingly complicated job of maintaining a farm. This new law promised to provide a free and open access education for rural, often poor, youths.[4]

Morrill and his fellow Republicans (the heirs to the Whig party) articulated a different intent. They defended the law as federal support to “advance economic activity through promoting agricultural science, disseminating useful knowledge, producing skilled free laborers, and elevating the competitiveness of America’s farms and factories.”[5]The act would “offer an opportunity…for a liberal and larger education to larger numbers, not merely to those destined to sedentary professions, but to those needing higher instruction for the world’s business…to guide and lead the industrial forces of a great nation.”[6] “To Justin Morrill, his land-grant college act was another internal improvement program in the Whig tradition, aimed at developing a modern capitalist economy in an upstart nation.”[7] The modern interpretation of what it means to be a land-grant institution merges those two views by offering the promise of social mobility and a commitment to advancing scientific knowledge to all the residents of a state.

1862

Few years have mattered more in the history of U.S. real estate than 1862. In May, Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act, which offered farmland to settlers willing to occupy it for five years. Six weeks later came the Pacific Railway Act, which subsidized the Transcontinental Railroad with checkerboard-shaped grants. The very next day, on July 2, 1862, Lincoln signed “An Act donating Public Lands to the several States and Territories which may provide Colleges for the Benefit of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts.” –Robert Lee and Tristan Ahtone, "Land-grab universities"

Although today we celebrate that mission of land grant colleges to provide upward social and economic mobility to all residents, Morrill was not particularly interested in the advancement of non-whites or women.[8] Even during the height of Reconstruction and certainly in the decades that followed, the social mobility promised by a college education “was a white prerogative” and “inherently male.”[9] Further, the financial support for this enormous expansion of federal aid to education was predicated on transferring to the states “government land,” in the case of western states, or issuing scrip for the selling of western lands in the case of eastern states. According to UC Riverside professor Margaret A. Nash, the Morrill Act must be understood as “an instrument of settler colonialism.”[10] That is, universities across the country were either built on or funded by the sale of appropriated native land across the west. More than eleven million acres of land was distributed to states for the establishment and support of land-grant colleges.[11] The damage, Nash notes, went beyond the dispossession; the availability of cheap land spurred western migration, increasing the population pressure on native lands and the systems of education it financed reproduced “dominant values” that favored patriarchy and white supremacy.[12]

Read more about the context of “Continental Colonialism” and the dispossession of Natives and Mexican Americans in the Southwest.

Thus, the legacy of the Morrill Act is complicated and its benefits cannot be taken for granted or assumed. The author’s intent to expedite “the rise of science in American higher education” and place the United States at the forefront of “modernization and productivity” has undoubtedly been realized.[13] And through the activism of proponents to expand access to higher education, a more equitable understanding of who should benefit from land-grant universities has also improved. The University of California recently announced its “Native American Opportunity Plan” to fully cover in-state tuition and student services fees for California undergraduate and graduate students who are enrolled in federally recognized Native American, American Indian, and Alaska Native tribes.[14] As noted in the 2019 HSI Taskforce report, “As a land grant university, UC Davis has a responsibility to offer an accessible and valuable education to California’s residents…As part of this land grant legacy, UC Davis plays a vital role as an engine of social mobility, education first-generation college-goers, children of immigrants and the economically disadvantaged.”[15] These should be the values that continue to guide future action.

Read the next article in this series:

Context: Chicana/o Student Protests in the 1960s

Top image: Playground, Blackhawk, California. Indigenous Caretakers: Chap-pah-sim; Co-to-plan-e-nee; I-o-no-hum-ne; Sage-womnee; Su-ca-ah; We-chil-la. Ownership Transfer Method: Seized by unratified treaty, May 28, 1851. For the Benefit of: University of Delaware. Lee and Ahtone, “Land-grab universities,” High Country News, March 30, 2020.

Read More:

Joseph A. Myers Center for Research on Native American Issues & Native American Student Development.(2021). The University of California Land Grab: A Legacy of Profit from Indigenous Land A Report of Key Learnings and Recommendations. University of California, Berkeley. Available at https://cejce.berkeley.edu/centers/native-american-student-development/uc-land-grab.

National Research Council. 1995. Colleges of Agriculture at the Land Grant Universities: A Profile. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/4980.

Robert Lee and Tristan Ahtone, “Land-grab universities,” High Country News, https://www.hcn.org/issues/52.4/indigenous-affairs-education-land-grab-universities, March 30, 2020.

Evelyn Nakano Glenn, “Settler Colonialism as Structure: A Framework for Comparative Studies of U.S. Race and Gender Formation,” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 1, n. 1 (January 2015): 52-72.

Jon Parmenter, "Flipped Scrip, Flipping the Script: The Morrill Act of 1862, Cornell University, and the Legacy of Nineteenth-Century Indigenous Dispossession," Cornell University and Indigenous Dispossession Project, https://blogs.cornell.edu/cornelluniversityindigenousdispossession/2020/10/01/flipped-scrip-flipping-the-script-the-morrill-act-of-1862-cornell-university-and-the-legacy-of-nineteenth-century-indigenous-dispossession/, accessed March 12, 2023.

Sharon Stein, “A Colonial History of the Higher Education Present: Rethinking Land-Grant Institutions through Processes of Accumulation and Relations of Conquest,” Critical Studies in Education 61, n. 2 (December 2017): 212-28.

[1] Nathan N. Sorber, Land-Grant Colleges and Popular Revolt: The Origins of the Morrill Act and the Reform of Higher Education (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018), 51.

[2] Sorber, Land-Grant Colleges and Popular Revolt, 46.

[3] Carl Lieberman, “The Constitutional and Political Bases of Federal Aid to Higher Education, 1787-1862,” International Social Science Review 63, n. 1 (Winter 1988): 7-9; Sorber, Land-Grant Colleges and Popular Revolt, 53-4.

[4] Sorber, Land-Grant Colleges and Popular Revolt, 2.

[5] Sorber, Land-Grant Colleges and Popular Revolt, 47.

[6] Justin S. Morrill, An Address in Behalf of the University of Vermont and State A cultural College, Delivered in the Hall of the House of Representatives, October 10, 1888, quoted in Sorber, Land-Grant Colleges and Popular Revolt, 2.

[7] Sorber, Land-Grant Colleges and Popular Revolt, 13.

[8] Sorber, Land-Grant Colleges and Popular Revolt, 49.

[9] Sorber, Land-Grant Colleges and Popular Revolt, 4, 150.

[10] Margaret A. Nash, “Entangled Pasts: Land-Grant Colleges and American Indian Dispossession,” History of Education Quarterly 59, n. 4 (November 2019): 447.

[11] Nash, “Entangled Pasts,” 451.

[12] Nash, “Entangled Pasts, 447.

[13] Sorber, Land-Grant Colleges and Popular Revolt, 4, 172-3.

[14] University of California Office of the President, “Native American Opportunity Plan,” https://admission.universityofcalifornia.edu/tuition-financial-aid/types-of-aid/native-american-opportunity-plan.html, accessed October 24, 2022.

[15] University of California, Davis HSI Taskforce, “Investing in Rising Scholars and Serving the State of California: What It Means for UC Davis to be a Hispanic Serving Institution,” https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5fk140g5#main, 16.