Thomas O'Donnell, Ph.D., Principal Analyst, Office of Academic Diversity

twodonnell@ucdavis.edu

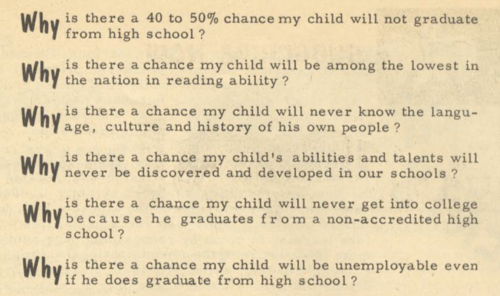

The abysmal education opportunities available to Chicanas/os in California combined with numerous other issues facing nonwhites in the United States in the 1960s that brought students across the country and at UC Davis out to protest. In fact, the same year the United Mexican American Students (UMAS) held its symposium, 1968, was an enormously significant year for demanding redress by the nation’s historically marginalized.

Early Youth Activism

Although student activism around the country and at UC Davis became more visible by the late 1960s, as noted in an earlier article, challenges to segregation and discrimination in education had been ongoing for many decades. And, according to Carlos Muñoz, activism by students stretches just as far back. He identifies Ernesto Galazara, a graduate student in history at Stanford University in 1929, as one of the founders of student activism that dedicated his life to advocating on behalf of Mexican immigrant and Mexican American workers.[1]

The brief period of optimism following the defeat of fascism and the unifying effects of patriotism during the Cold War motivated young Mexican American activists, many of them veterans, to promote a more integrated and socially-just society. However, the failure of many white Americans to fully comprehend the lessons of Hitler and the Holocaust quickly dampened that enthusiasm. Further, the conformist, anti-radical politics of the 1950s cast suspicion on social justice causes that might be labeled as “communist.”[2]

Civil Rights Movement

By 1968, the modern Civil Rights Movement (CRM) had been ongoing for nearly two decades–Rosa Parks work with the NAACP investigating the rape of black women in the South started a decade before her more famous bus ride in Montgomery, Alabama.[3] In his well-respected study of youth in the Chicano Movement, Carlos Muñoz Jr. explains that the CRM “created a political atmosphere beneficial to Mexican American working-class youth, for it gave them more access to institutions of higher education.”[4] And, in her study of the Chicana/o Student Movement in higher education, Marisol Moreno asserts, “Students were indispensable to the development and the mobilization of the Chicano Movement. With access to higher education-a social institution that encouraged dialogue and critical thinking…student activists were able to spend considerable time and energy discussing movement politics and Chicano identity.”[5]

As important and effective as the CRM was, Mexican American activist began to believe that the objectives of African American leaders and organizations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) did not address their historical and cultural concerns.[6] Additionally, activists with the earlier Mexican American Movement began to also sour on the lack of Chicana/o-specific solutions supported by President Johnson’s administration and his Great Society initiative and the Democratic Party more generally.[7]

This new “Chicano” Movement, began to diverge dramatically from a previous generation of Mexican American activism by rejecting the notion of assimilating into the white mainstream culture, promoting more radical ideologies and actions in response to racial discrimination, and featured students more prominently.[8]

“Unification calls for education”–The East Los Angeles Walkouts

The confluence of more radical actions by protestors, the involvement of more youths, and the critique of structural racism including public education led to more direct attacks on state institutions.[9] Moreno notes “Chicana/o youth linked the inferior conditions of their public schools, and its failure to prepare a majority of Mexican Americans for admission to a four-year university, to the larger pattern of racial discrimination experienced by working class Mexican communities throughout the Southwest.”[10]

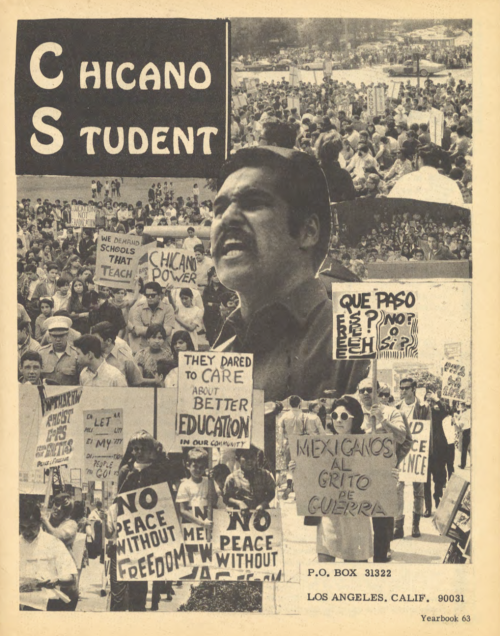

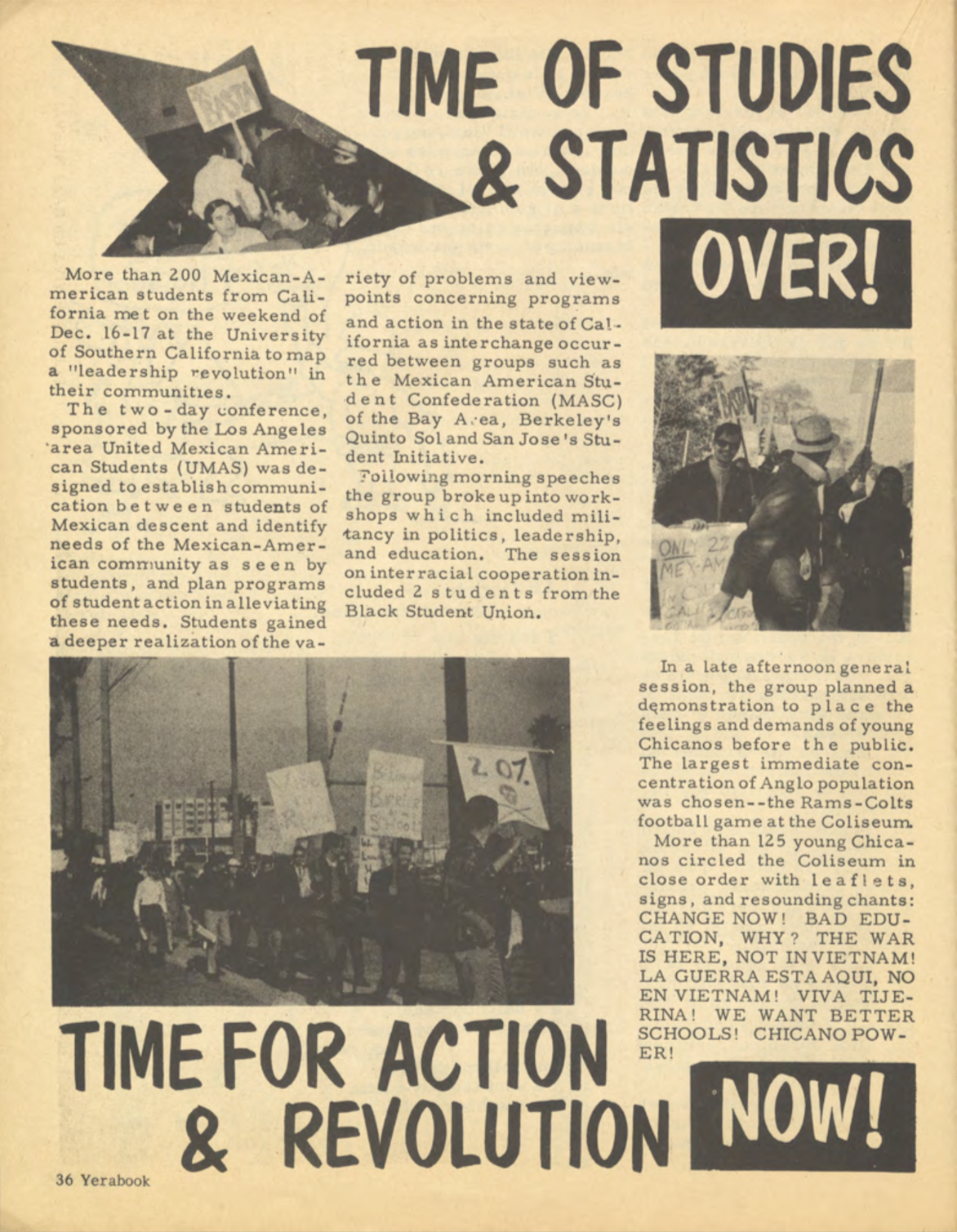

In spring 1968, the anger over that failure, what Wheatland High School art teacher Jose Montoya criticized as the constant derailment of Chicano student aspirations, instigated what became known as the East Los Angeles Walkouts or “Blowouts.” Over the course of a week, “22,000 students had stormed out of class, delivered impassioned speeches and clashed with police.”[11]

The underground newspaper, La Raza, published an account of the protests by some of the students who participated.

The underground newspaper, La Raza, published an account of the protests by some of the students who participated.

BLOW OUTS were staged by us; Chicano students, in the East Los Angeles High schools protesting the obvious lack of action of the part of the LA School Board…We want immediate steps take to implement bi-lingual and bi-cultural education for Chicanos. WE WANT TO BRING OUR CARNALES HOME. Teachers, administrators, and staff should be educated; they should know our language, (Spanish), and understand the history, traditions, and contributions of the Mexican culture. HOW CAN THEY EXPECT TO TEACH US IF THEY DO NOT KNOW US?[12]

The students met with the school board to present their demands, most of which were not met and there was little structural change in the immediate aftermath of the Walkouts. Reflecting on the Walkouts 50 years later, journalist Louis Sahagún notes that “perhaps the walkouts’ greatest accomplishment was fostering in the Mexican American community a sense of possibility–the realization that a just cause sometimes requires speaking up.”[13]

And it was that realization that quickly spread throughout the Chicana/o community and ignited protests across the state and at UC Davis.

Read the next article in this series:

Chicanas/os Begin to Organize at UC Davis

Top image: Photograph from 1968 Los Angeles, protesting discriminatory education policies. La Raza Yearbook, September 1968, page 16.

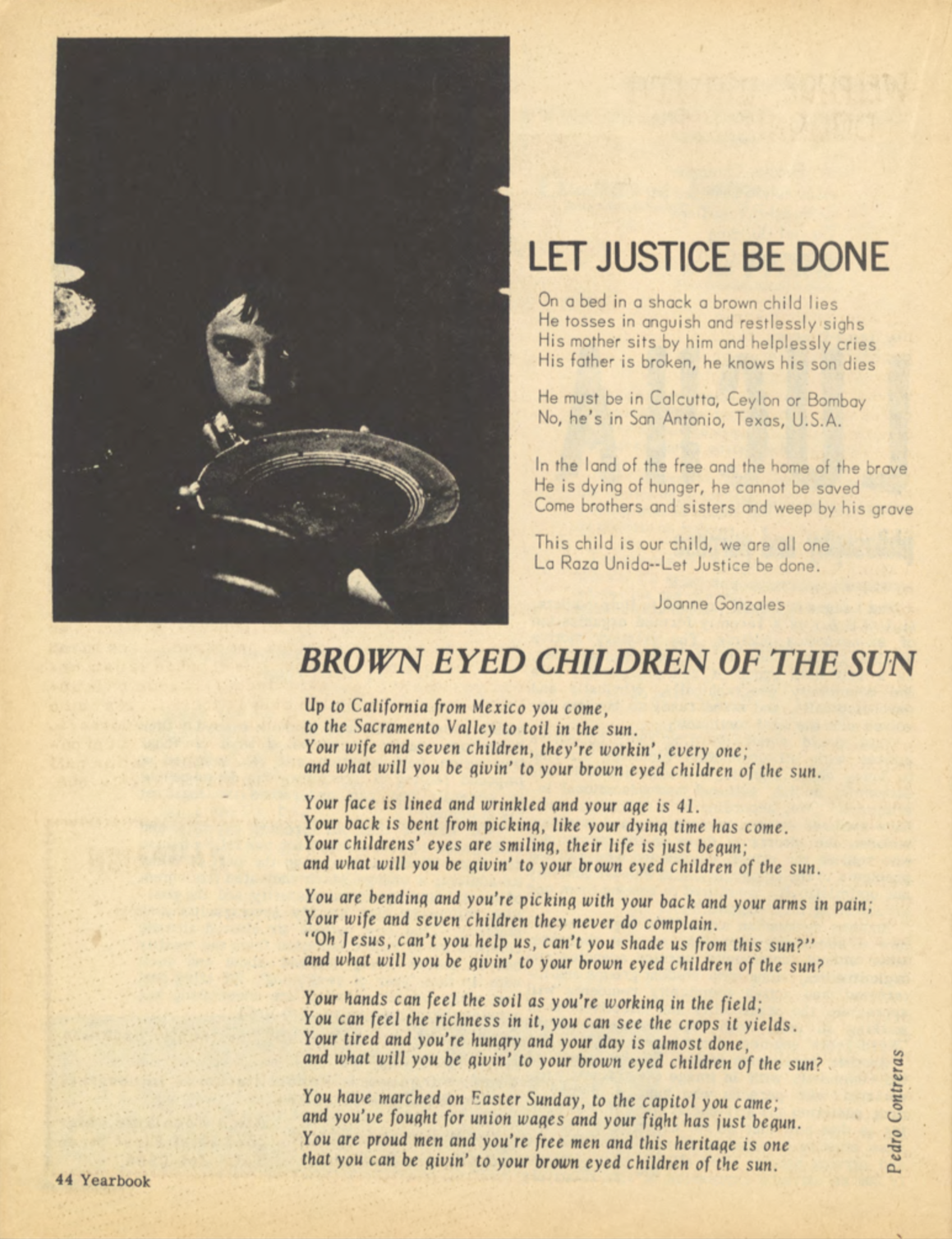

Pages from La Raza's 1968 Yearbook.

Read More:

Dolores Delgado Bernal, “Grassroots Leadership Reconceptualized: Chicana Oral Histories and the 1968 East Los Angeles School Blowouts,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 19, n. 2 (1998): 113-142.

La Raza Yearbook (Los Angeles: Chicano Press Association, 1968).

Library of Congress, A Latinx Resource Guide: Civil Rights Cases and Events in the United States, “1968: East Los Angeles Walkouts.”

Michael Soldatenko, “Mexican Student Movements in Los Angeles and Mexico City 1968.” Latino Studies 1, n. 2 (2003): 1-17.

[1] Carlos Muñoz Jr., Youth, Identity, Power: The Chicano Movement, Rev. ed. (New York: Verso, 2007), 27. Image: excerpt from La Raza newspaper, September 1968.

[2] Muñoz, Youth, Identity, Power, 63.

[3] Danielle L. McGuire, At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance–A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010).

[4] Muñoz, Youth, Identity, Power, 65.

[5] Moreno, “The Chicana/o Student Movement,” 9.

[6] Muñoz, Youth, Identity, Power, 66.

[7] Muñoz, Youth, Identity, Power, 69.

[8] Muñoz, Youth, Identity, Power, 22. Christopher Tudico argues that "assimilation" was not strictly the objective of earlier activists of the pre-1960s. "Before We Were Chicanas/Os: The Mexican American Experience in California Higher Education, 1848-1945," dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 2010.

[9] Subhead quote from “Raza Unida Party: Call for Self Determination,” Third World News, May 10, 1971.

[10] Marisol Moreno, “‘Of the Community, For the Community’: The Chicana/o Student Movement in California’s Public Higher Education, 1967-1973,” (PhD diss., University of California, Irvine, 2009), 4.

[11] Louis Sahagún, “East L.A., 1968: ‘Walkout!’ The day high school students helped ignite the Chicano power movement,” Los Angeles Times, March 1, 2018.

[12] La Raza Yearbook (Los Angeles: Chicano Press Association, 1968), 16.

[13] Louis Sahagún, “East L.A., 1968: ‘Walkout!’ The day high school students helped ignite the Chicano power movement,” Los Angeles Times, March 1, 2018.