Thomas O'Donnell, Ph.D., Principal Analyst, Office of Academic Diversity

twodonnell@ucdavis.edu

The 1970 Chicano Moratorium

In addition to the protests unfolding in California in the late 1960s we previously covered that formed the context for the development of the Chicano Student Movement, another major event took place in late August of 1970 that must be credited with further motivating student involvement.

Carnales Home

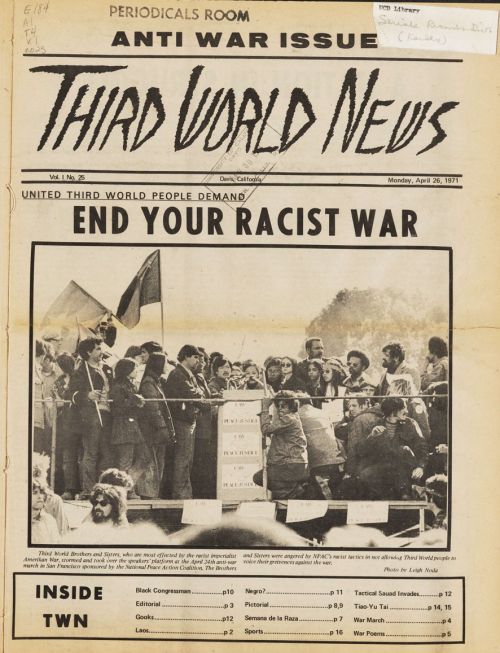

“We want our carnales home,” wrote Robert Aguilar in 1971, a frequent contributor to the Third World News, “to help us carry on the struggle for social justice, the struggle for ‘la Causa.’” Aguilar was responding to an anti-war “March for Peace” rally in San Francisco. In the preceding issue of that publication, the “Anti War Issue,” Gloria Hernandez, the UC Davis MEChA Secretary and Chicana Editor of Third World News, reminded readers that more than 10,000 Chicanos had been killed in the war in Vietnam and at the same time in the US, “Billions upon billions of our tax dollars are spent on the war instead of fighting unemployment, poor housing, creating child care centers, better education and various other community programs.” She also noted that the very first POW of the war “was a CHICANO–and he is still there.”

That fact is where UC Davis history professor emerita (and current professor of ethnic studies at UC Berkeley) Lorena Oropeza begins her book, ¡Raza Si! !Guerra No!: Chicano Protest and Patriotism during the Viet Nam War Era. The North Vietnamese captured Everett Alvarez, a pilot with the navy, in August 1964 and he remained a prisoner of war for eight-and-half-years. During that time, his sister, Delia Alvarez, who like many other Chicanas/os, was “initially uncritical about American involvement in Viet Nam,” became active in the Chicano Movement and an anti-war protestor (1). Oropeza concludes her examination of the Chicano responses to the war, which she argues, “fundamentally shaped the Chicano movement’s challenge to long-held assumptions about the history of Mexican origin people and their role within American society,” with a chapter on the Chicano Moratorium March of August 1970 (5).

A Catalytic Moment

On the morning of August 29, 1970 as many as 30,000 protesters gathered in East Los Angeles and marched down Whittier Boulevard to protest the disproportionate number of Chicanos killed in the war in Vietnam and “opposing racism and economic discrimination in the U.S.” Oropeza quotes the Los Angeles National Chicano Moratorium Committee, which insisted “Our front line is not in Vietnam but in the struggle for social justice in the U.S.” (147). And although the day started with great energy, excitement, and hope, it ended tragically.

“POLICE RIOT THWARTS MORATORIUM,” announced an article in the Third World News shortly after the day’s events. “L.A. County Sheriff's deputies, joined by reinforcements from the city's police department, charged the park where the demonstration’s concluding rally was being held, a decision that turned the demonstration into a battlefield. Within a matter of minutes, the day's tremendous feelings of hope, joy, and pride dissolved into fear, anger, and sorrow” (Oropeza, 147). Writing for the Los Angeles Times on the occasion of the Moratorium’s fiftieth anniversary, Daniel Hernandez referred to the day as “a catalytic moment.” Despite the anger many in the community continued to feel about that day and the calls to action it continued to inspire, both Hernandez and Oropeza assert that the day also represented a “serious setback” and the “beginning-of-the-end of the Chicano movement.”

Nevertheless, journalists and editors of the Third World Forum continued to memorialize the march. In 1977, they pointed to the police response as “another example of Chicanos were treated unfairly in the U.S.” and it reinforced a resolve to continue the fight. On the occasion of the ten-year anniversary–well after the end of the Vietnam War–they invited readers to participate in the commemorative demonstration planned for later that year. In keeping with the original intent of the Moratorium, a demand for the end of racism against Chicanas/os, “issues such as police repression and Migra [INS/immigration enforcement] attacks on undocumented workers” would be addressed. Additionally, UC Davis students at the time such as Neptaly “Taty” Aguilera who attended the Moratorium–and continues to this day to advocate on behalf of Chicana/o and Latina/o students, faculty, and staff–have called it one of several “life changing experiences,” that motivated their student activism. (Aguilera’s quote comes from his oral interview with a student in professors Natalia Deeb-Sossa and Lina Mendez’s Community-Based Participatory Research course in spring 2021.)

There are many more stories to tell about the 1970 Chicano Moratorium and its legacy at UC Davis. If you have an idea or work to submit on the topic, please let us know!

Stay tuned for our next article in the series in recognition of Cesar Chavez Day (March 28, 2023) highlighting his several visits to campus over the years.

Read more:

“The Chicano Moratorium 50 Years Later,” Los Angeles Times, https://www.latimes.com/projects/chicano-moratorium/. An interactive an in-depth look at the day and its reverberations in politics and culture even decades later.

“Chicano Moratorium 50th Anniversary Project,” UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center hosts an all-in-one go-to source for instructors and students to learn more about what happened that day, why it happened, and how it changed the course of the civil rights movement across the United States for the Chicano/Latino community. https://chicanomoratorium.omeka.net.

Lorena Oropeza, ¡Raza Si! ¡Guerra No! Chicano Protest and Patriotism during the Viet Nam War Era (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).